Section I. A Little Background

When a company sells a product, they expect to get paid. That makes enough sense! The customer will either pay for that product immediately or the company will extend credit to the customer, letting them pay later. When a company does extend credit, they expose themselves to risk because it is entirely possible that not every customer will be able to pay their bill. When this happens, when a customer is unable or unwilling to pay their bill, it is called a bad debt. (Other common names include uncollectible account, provision for uncollectible account, and doubtful account. Here we will primarily use bad debt to refer to such accounts.)

While certainly unwanted, bad debts are considered a cost of doing business. Management realizes that if extending credit some accounts may go uncollected. It is up to the managers to decide whether the benefit of extending credit outweighs the potential risk of not ever collecting that money. If management decides to extend credit, it must plan for bad debts.

Bad debts are an expense for the company. If we sell merchandise and do not get paid for it, that negatively affects our bottom line. The matching principle states that expenses must be recognized in the same period as the revenues that they generate. To follow the matching principle, we must recognize the bad debt expense in the same period as the related sale, i.e., the sale to the customer who is not going to pay. This presents an interesting problem: we must recognize an expense at the end of this period (as an adjusting entry), yet we don’t know which accounts are going to go bad. Accounts may not go bad until a year or two from now. A customer may decide not pay for a sale many years later. So how are we supposed to recognize an expense now for an event that has yet to happen, may not happen, and even if it does, we don’t know when it will happen or for how much?

The answer: guess.

Well, more accurately: estimate. But really, those two are the same thing. An estimate is just a better guess than a guess. We’ll go over how to guess, but for now we need to learn a little about Bad Debt’s brother account: the Allowance for Bad Debts.

Section II. An Allowance

If we know that some accounts are not going to be collected, we can’t rightly present the Accounts Receivable account at full value on the Balance Sheet, because we don’t actually think we are going to be able to collect all of those accounts. We would be presenting our most hopeful value, which isn’t conservative, so we need to present the value that we actually think we are going to be able to collect. This is called the net realizable value.

We can’t mess with the Accounts Receivable account directly because we don’t know which accounts are going to go bad (i.e., be uncollectible), we just know that some are. So rather than directly adjust some of the accounts, we are going to have an allowance that reduces the total value of the Accounts Receivable account. The Allowance for Bad Debts account is that account.

Allowance for Bad Debt is a contra-asset whose only purpose is to bring the Accounts Receivable account down to the reportable net realizable value. (Note, that like bad debts, the Allowance for Bad Debt has multiple names, including Allowance for Uncollectible accounts and Allowance for Doubtful accounts. They all mean the same thing and can be used interchangeably.) That gives us the following formula:

| Accounts Receivable |

| (Allowance for Bad Debt) |

| Net Realizable Value |

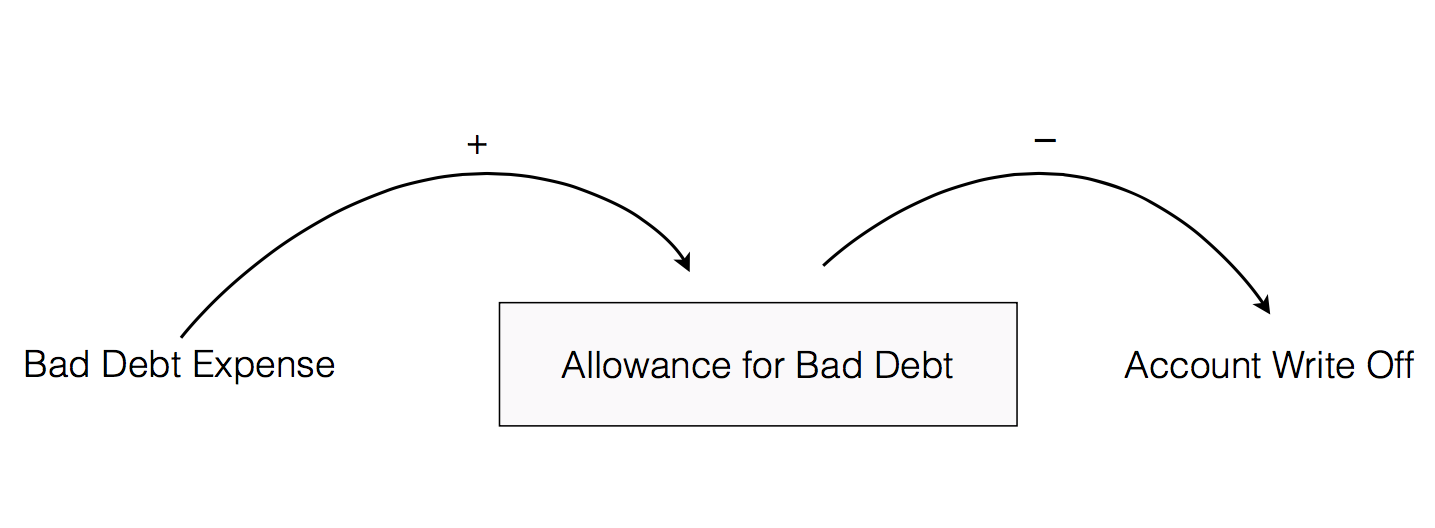

We now know the purpose and usage of both the Allowance for Bad Debt account and bad debt expense, but how do these two accounts actually work together?

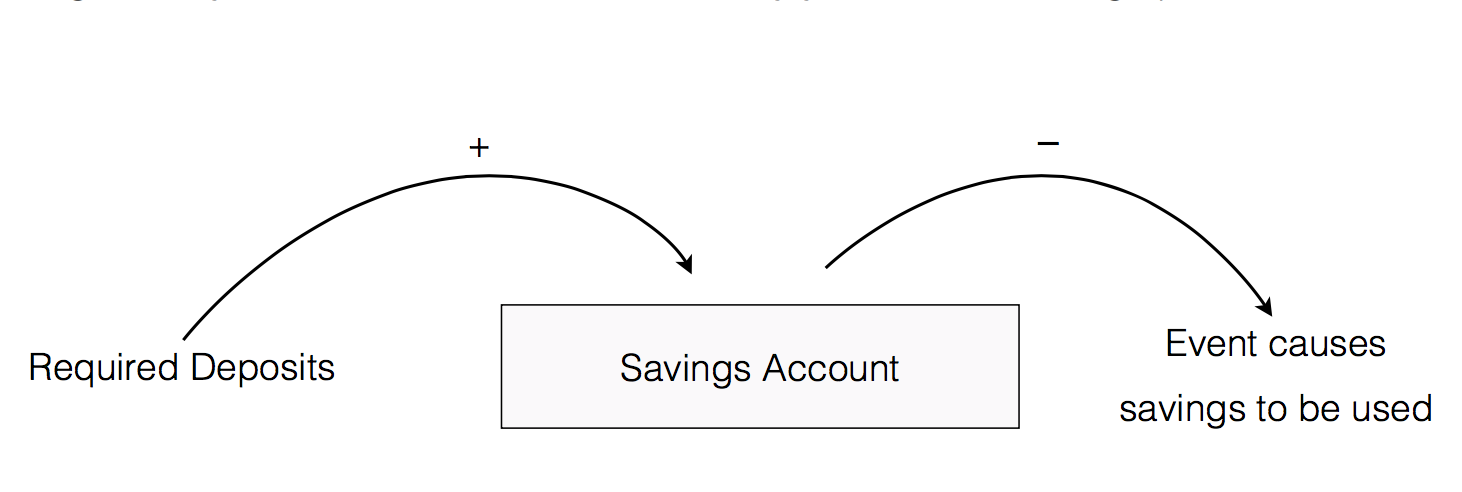

Think of a mandatory savings account where you are required to put in a certain amount each month: you deposit, deposit, deposit, and eventually an event comes along where you withdrawal some of that money you’ve been storing up.

This is symbolic of the relationship between bad debt expenses and the Allowance for Bad Debt. Every period we must recognize an expense because we know that eventually some accounts are going to go bad. We don’t know when or for how much, but we believe it’s coming and are therefore required to recognize an expense. So we recognize the expense and then what? No account has gone bad yet, but we’re ready just in case one does. We increase our “savings account,” the Allowance for Bad Debt. (Note that this is a metaphor, we are not actually setting aside cash.)

We store it up until an account actually does go bad, in which case we are ready, no further expense necessary! We’ve already expensed all we needed to. Consider the name of the account: "Allowance for Bad Debt." It's the perfect logical name: We are allowing for the case when an account becomes uncollectible, i.e., a bad debt. Hence: Allowance for Bad Debt.

With the big picture in mind, let’s get down to the actual accounting details: the journal entries.

Section III. Writing in Your Journal

As you might have assumed, "bad debt expense" is an expense account. Expense accounts are always debited. Allowance for Bad Debt is a contra-asset, as discussed above; it reduces the net value of Accounts Receivable. Because assets are debited, contra-assets are credited. We’ll cover how to calculate the estimate later, but for now assume that the bad debt expense is $1,000. The journal entry would be as follows:

Journal Entry:

| Bad Debt Expense | 1,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 1,000 |

We increase the expense by debiting it and we also increase the allowance by crediting it. It is important that you understand this journal entry as this will always be the journal entry to record bad debt expense. Increase the expense, increase the allowance. The t-accounts are shown below.

| Bad Debt Expense | |

| 1,000 | |

| Allowance for Bad Debts | |

| Beg Bal | |

| 1,000 | |

The Allowance for Bad Debt (ABD) account will likely have a beginning balance already in the account, while the bad debt expense account will likely be empty. The bad debt expense account is closed at the end of every year, while the ABD account stays open from year to year, because it is a balance sheet account.

Let’s now turn our attention to the most difficult part of bad debt expenses, the estimating of the actual expense.

Section IV. How to Guess: An Intro

There are two ways to estimate the amount of the bad debt expense. The first is called the Income Statement Method and the second is, understandably, the Balance Sheet Method. Like most things in accounting, they are named that way for a very logical reason.

Consider the income statement: the income statement deals only in temporary accounts. Every account on the income statement is closed out at the end of the year.

Consider the balance sheet: the balance sheet deals only in permanent accounts, every account has an ending balance that is rolled over to the next year.

This is a very important distinction to note as we look at the two methods used to calculate bad debt expense.

Section V. How to Guess: The Income Statement Method

When calculating bad debt expense based on the Income Statement method, you will use a temporary account to determine a temporary account. This method is the easiest of the two methods. First, you are given a management estimate of the percentage of credit sales that are expected to be uncollectible, e.g., 2%. To calculate the bad debt expense, simply take the net credit sales from the period and multiply it by the given percentage. Sales is a temporary account, and when multiplied by the stated percentage, a temporary account is the result: bad debt expense.

A basic example is provided below:

Step 1: Multiply net credit sales by given percentage

| 600,000 | * | 0.02 | = | 12,000 |

| Net Credit Sales | * | Percentage | = | Bad Debt Expense |

Step 2: Journal Entry:

| Bad Debt Expense | 12,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 12,000 |

As you can see, this is a very basic example. One way that it could be more complicated is by requiring you to calculate net credit sales. Net credit sales is calculated as total credit sales less discounts, returns, and allowances.

| Total Credit Sales |

| (Returns) |

| (Discounts and Allowances) |

| Net Credit Sales |

In the following example In the following example, you are given gross credit sales instead of net.

Step 1: Calculate net credit sales.

| Total Credit Sales | 600,000 |

| (Returns) | (40,000) |

| (Discounts and Allowances) | (10,000) |

| Net Credit Sales | 550,000 |

Step 2: Multiply net credit sales by given percentage

| 550,000 | * | 0.02 | = | 11,000 |

| Net Credit Sales | * | Percentage | = | Bad Debt Expense |

Step 3: Journal Entry:

| Bad Debt Expense | 11,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 11,000 |

That’s about as hard as the Income Statement method can get. All you have to do is multiply the net credit sales by the given percentage and the result is the bad debt expense. Pause for a second and think about why we are multiplying by net credit sales instead net sales?

Consider this: an account cannot be uncollectible if the customer paid cash, right? Because the account has already been collected! So if we multiplied the uncollectible percentage by net sales instead of net credit sales, we've included sales that have already been collected, namely, cash sales.

Now extend that logic to the following question: why net credit sales instead of gross credit sales? Why are we subtracting returns and discounts and allowances? In this whole process, what we are trying to do is determine how much of the money that we are rightfully owed is not going to be paid. Are we owed money from customers who return the merchandise? Nope. And if we give a 10% discount, are we owed that 10%? Nope. So if we were to include returns or discounts and allowances in our calculation, that wouldn't make any sense at all.

Now that you've mastered the Income Statement method, let's look at the Balance Sheet method. It's slightly more complicated, involving an extra step.

Section VI. How to Guess: The Balance Sheet Method

Whereas under the Income Statement method we multiplied a percentage by a temporary account to result in a temporary account, under the Balance Sheet method we will use a permanent account to result in a permanent account.

The basis for calculating bad debt under the Balance Sheet method is the Accounts Receivable account. (Remember, the basis for calculation using the Income Statement method was net credit sales.) Like the Income Statement method, a management estimated percentage will be provided based on historical data. This percentage is management’s best guess about what amount of the accounts receivable will be uncollectible, not the amount of credit sales uncollectible. The percentage is then taken and multiplied by the ending accounts receivable.

| Accounts Receivable | |

| 100,000 | 480,000 |

| 600,000 | |

| 220,000 | |

| ABD | |

| 6,000 | |

| 220,000 | * | 0.05 | = | 11,000 |

| Ending A/R | * | Percentage | = | ?? |

What is the result of the calculation: Ending A/R * Percentage? The accounts receivable account is a permanent account, so the result cannot be bad debt expense; a permanent account can’t result in a temporary account. There is, however, a permanent account that is closely related to bad debt expense: the allowance for bad debt.

Because the allowance for bad debt represents the amount that is expected to be uncollectible, then it makes sense that if managements expects to not be able to collect 5% of accounts receivable, the allowance for bad debt must be 5% of A/R. Take a look at the next example:

| Accounts Receivable | |

| 100,000 | 480,000 |

| 600,000 | |

| 220,000 | |

| ABD | |

| 6,000 | |

| 220,000 | * | 0.05 | = | 11,000 |

| Ending A/R | * | Percentage | = | Ending ABD |

Step 2: Take the result of step one and set it as the ending ABD.

| ABD | |

| 6,000 | |

| 11,000 | |

Once the ending ABD has been solved for, all that’s left to do is calculate the missing amount. In this example, how do you get from 6,000 to 11,000? Add 5,000.

| ABD | |

| 6,000 | |

| ??? | |

| 11,000 | |

| ABD | |

| 6,000 | |

| 5,000 | |

| 11,000 | |

Step 4: Record the appropriate adjusting entry.

| Bad Debt Expense | 5,000 |

| Allowance for Bad Debt | 5,000 |

The missing amount, that amount you just solved for, is the bad debt expense. Think about it, how is the ABD account increased? If you look back to the very beginning of the guide, you’ll see that the ABD account is increased by the same amount as the bad debt expense. Those two always work hand-in-hand.

Once you solve for the ending ABD, the only way to get to that amount is by increasing the bad debt expense, which is why the journal entry is for the 5,000 difference, not the 11,000 total. 11,000 is where the account needs to end, not what needs to be added to the account. Remember, we used ending A/R to calculate then ending ABD, so we need to adjust to get to that ending amount (11,000).

The balance sheet method can be used with the ending A/R or what’s called an aging of receivables. It’s the exact same idea, just broken down a bit further. The idea behind the aging of receivables is that as accounts get older, they are less likely to be collected.

Example: For accounts less than 30 days old, collectibility is 98%. Accounts between 30-60 days, 94%. For accounts older than 60 days, collectibility falls to 70%.

Given the following information, calculate the ending value in the allowance for bad debt account.

| Age of Account | Value |

|---|---|

| 0-30 | 40,000 |

| 30-60 | 8,000 |

| 60+ | 6,000 |

| Age of Account | Value | Percentage | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-30 | 40,000 | 0.02 | 8,000 |

| 30-60 | 8,000 | 0.06 | 480 |

| 60+ | 6,000 | 0.30 | 1,800 |

| Total | 10,280 |

Once you have the ending amount for the ABD account, you can carry on to calculate the bad debt expense as we have already learned.

The balance sheet method therefore has two variations. One uses the ending accounts receivable amount and the other breaks down the accounts receivable account by age. Other than that, there is no difference at all.

Here’s a high-level overview of the two main methods:

Percentage * Net Credit Sales

↓

equals

↓

Bad Debt Expense

↓

done!

Percentage * A/R

↓

equals

↓

Ending ABD

↓

adjustment is

↓

Bad Debt Expense

Using the Income Statement method, the given percentage is multiplied by net credit sales, resulting in the bad debt expense. The balance sheet method uses accounts receivable to calculate the ending allowance for bad debt. The adjustment required to get the ABD account to that ending balance is the bad debt expense.

Section VI. Writing Off and Reinstating Accounts

When an account does finally go bad, when it is determined that it won’t be collected, the account should be written off. Writing off an account has no impact on the income statement because the expense has already been taken. Additionally, it has no impact on the net realizable value of the accounts receivable, because the allowance for bad debt already reduces the net realizable value. Writing off an accountis very simple, you simply have to reduce the accounts receivable account as well as the allowance account.

Journal Entry:

| Allowance For Bad Debt | 10,000 |

| Accounts Receivable | 10,000 |

A reinstatement occurs when an account that has already been written off is paid. It is possible that years after an account has been deemed uncollectible, the customer finally makes payment. To reinstate that account, the allowance for bad debt must be increased to reverse the effect of decreasing the allowance when the account was originally written off.

Journal Entry:

| Cash | 10,000 |

| ABD | 10,000 |

Cash is increased because an account won’t be reinstated until it is paid off, i.e., cash is received.

Section VII. Summary

To comply with the matching principle, companies must record a bad debt expense in the period during which they make sales on credit. Because they don’t know to what extent the accounts will be uncollectible, they must make an estimate using one of two methods: the Income Statement method and the Balance Sheet method.

Using the Income Statement method, net credit sales is multiplied by a given percentage (based on management’s estimates) and results in the bad debt expense. Alternatively, under the Balance Sheet method, a given percentage is multiplied by accounts receivable to give us the ending Allowance for Bad Debt. Whatever amount is required to adjust the account to its proper ending balance is the bad debt expense.

To write off an account, simply reduce accounts receivable and reduce the allowance. To reinstate an account, increase the allowance and increase cash.